⬇️ Pidgin | ⬇️ ⬇️

EnglishMammoth Mysteries Unraveled: Da Tale of Elma 🐘

Advertisement

SKIP DA ADVERTISEMENT

You stay get one preview of dis article while we stay checking your access. When we done, da full article going load.

Origins

Scientists stay peepin’ at da layers of minerals left behind on mammoth tusks fo’ estimate where da hulking animals wen spend their days.

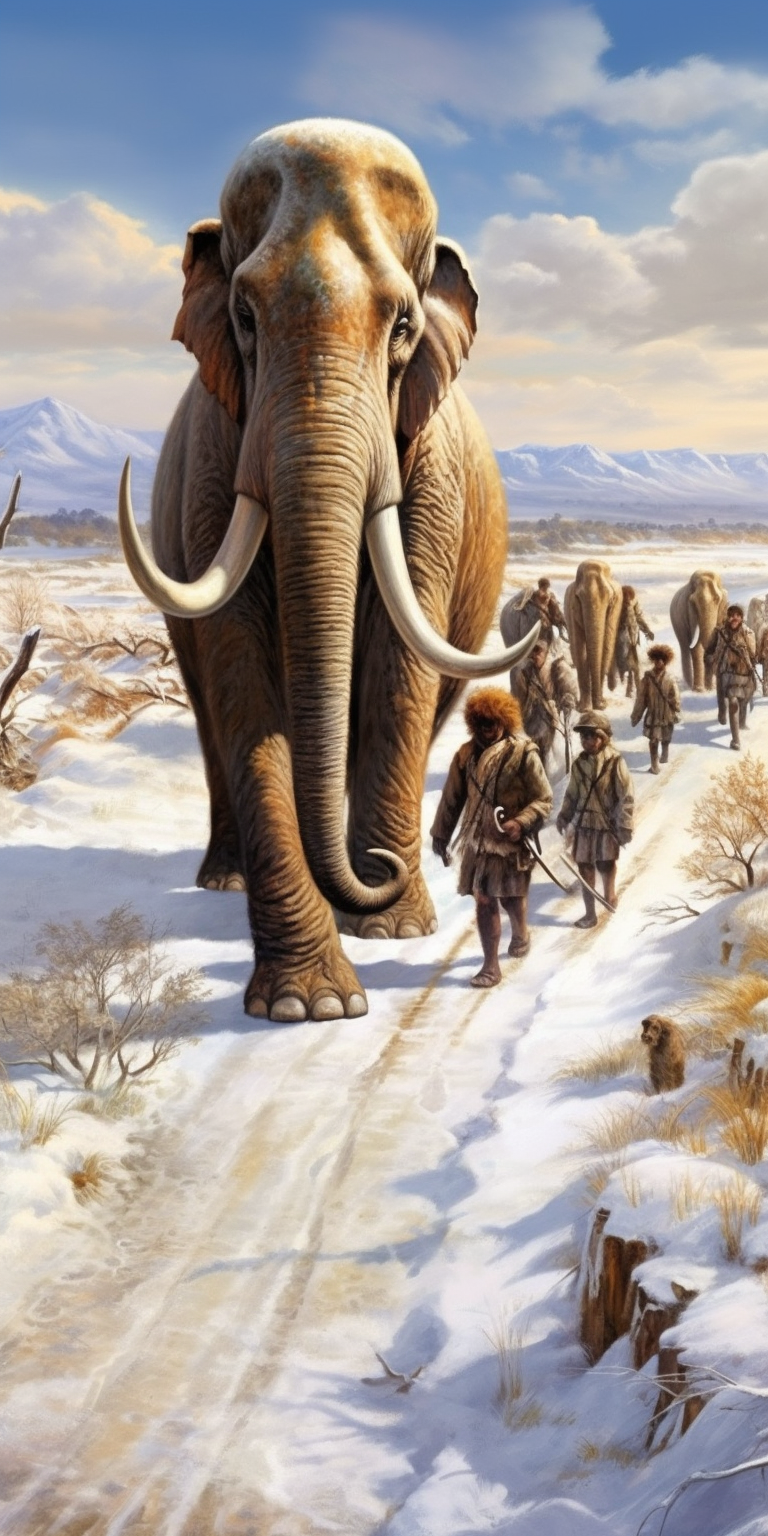

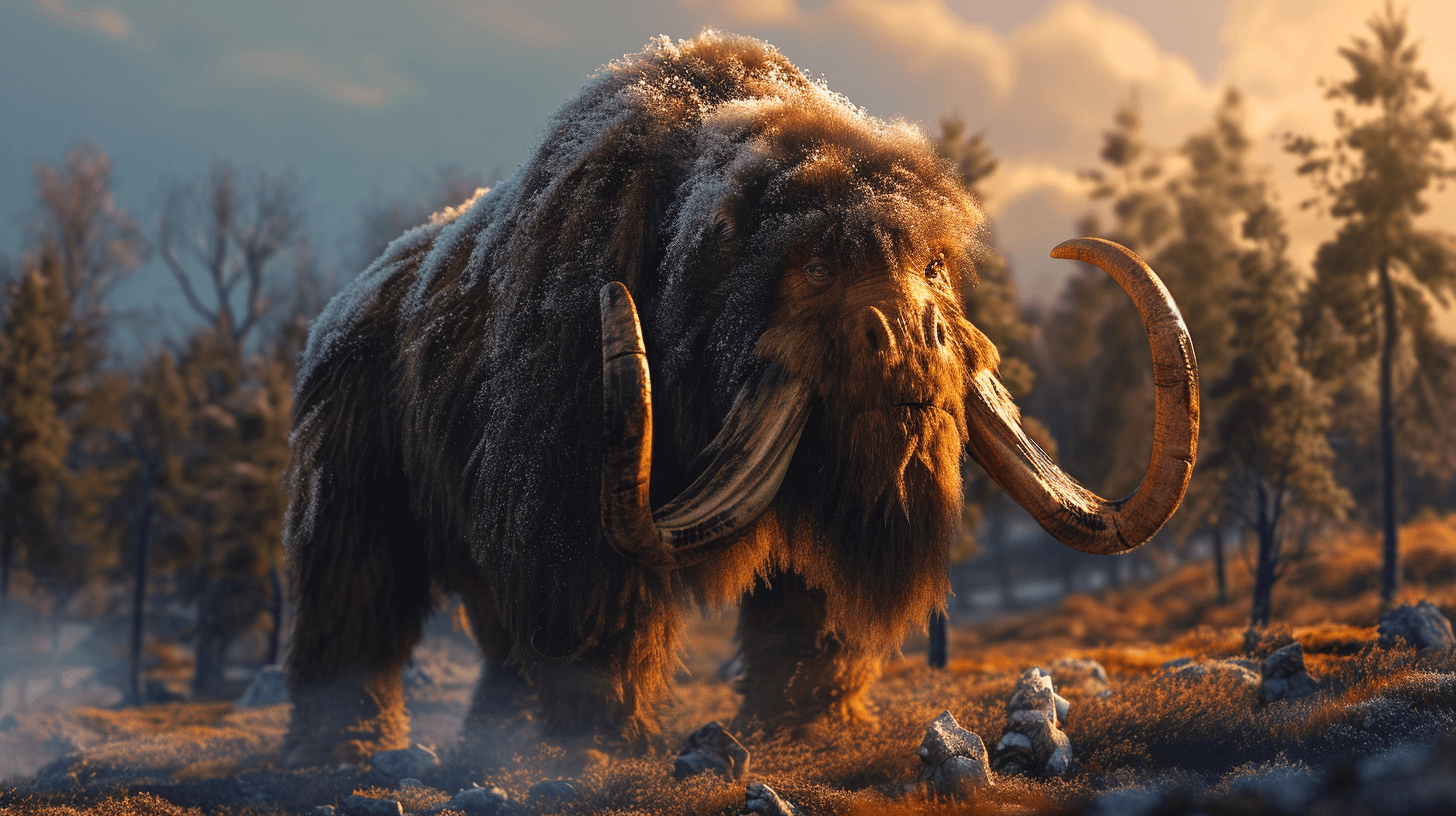

An artist’s reconstruction of mammoths crossing dunes north of da Swan Point archaeological site in Alaska 14,000 years ago.Credit…Julius Csotonyi/University of Alaska Fairbanks

Scientists wen write down da biography of one 14,000-year-old wahine woolly mammoth by analyzing da chemicals in her tusk.

Da animal, called Elma, wen born in what stay da Yukon now, and she stay near her birthplace fo’ about ten years before she wen move hundreds of miles west into central Alaska, da study wen find. Dass where she stay until she about 20, when most likely hunters wen take her down.

Scientists stay starting fo’ tell dem ancient stories by looking at da layers of minerals dat wen pile up each day on da outside of da tusks of mammoths and mastodons. As researchers look at mo’ tusks, dey hope fo’ settle some of da biggest questions ’bout how da hulking mammals wen survive fo’ hundreds of thousands of years. Dey also gathering clues to how mammoths and mastodons wen die out at da end of da Ice Age — maybe with some help from humans.

“There get answers out there,” said Joshua Miller, one University of Cincinnati paleoecologist who neva involved in da new study but who wen cut open one mastodon tusk in Indiana. He said gotta look at plenny tusks dat spanned thousands of years.

“We stay just starting fo’ build ’em,” Dr. Miller said, “and dass exciting.”

Woolly mammoths wen grow their tusks same like living elephants. Every day, one thin, cone-shaped layer of minerals wen pile up on da tip.

“I like fo’ describe ’em as ice cream cones stacked on top of each oddah,” said Matthew Wooller, director of da stable isotope facility at da University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Thank you fo’ your patience while we make sure you get access. If you stay in Reader mode, please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe fo’ all of Da Times.

Thank you fo’ your patience while we make sure you get access.

Already one subscriber? Log in.

Want all of Da Times?

NOW IN ENGLISH

Unlocking Ancient Stories: How Scientists Decode Mammoth Tusks

<p><strong>Mammoth Mysteries Unraveled: The Tale of Elma</strong></p><p>Advertisement</p><p>SKIP THE ADVERTISEMENT</p><p>You will get a preview of this article while we check your access. Once we are done, the full article will load.</p><p>Origins</p><p>Scientists are examining the layers of minerals left behind on mammoth tusks to estimate where the massive animals spent their days. An artist’s reconstruction of mammoths crossing dunes north of the Swan Point archaeological site in Alaska 14,000 years ago. Credit…Julius Csotonyi/University of Alaska Fairbanks. Scientists have written the biography of a 14,000-year-old female woolly mammoth by analyzing the chemicals in her tusk.</p><p>The animal, named Elma, was born in what is now the Yukon, and she remained near her birthplace for about ten years before moving hundreds of miles west into central Alaska, the study found. That’s where she stayed until about 20, when most likely hunters took her down.</p><p>Scientists are beginning to tell these ancient stories by examining the layers of minerals that accumulated each day on the outside of the tusks of mammoths and mastodons. As researchers look at more tusks, they hope to settle some of the biggest questions about how the massive mammals survived for hundreds of thousands of years. They are also gathering clues as to how mammoths and mastodons died out at the end of the Ice Age — perhaps with some help from humans.</p><p>“There are answers out there,” said Joshua Miller, a University of Cincinnati paleoecologist who was not involved in the new study but who once cut open a mastodon tusk in Indiana. He said it was necessary to look at many tusks that spanned thousands of years.</p><p>“We are just beginning to build them,” Dr. Miller said, “and that’s exciting.”</p><p>Woolly mammoths grew their tusks in a similar manner to living elephants. Every day, a thin, cone-shaped layer of minerals accumulated on the tip.</p><p>“I like to describe them as ice cream cones stacked on top of each other,” said Matthew Wooller, director of the stable isotope facility at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.</p><p>Thank you for your patience while we make sure you get access. If you are in Reader mode, please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.</p><p>Thank you for your patience while we make sure you get access.</p><p>Already a subscriber? Log in.</p><p>Want all of The Times?</p>