🦴🌍 Choke New Kine Tings ‘Bout How Da Firs’ Kine Humans Wen’ Come ‘Bout 🧬

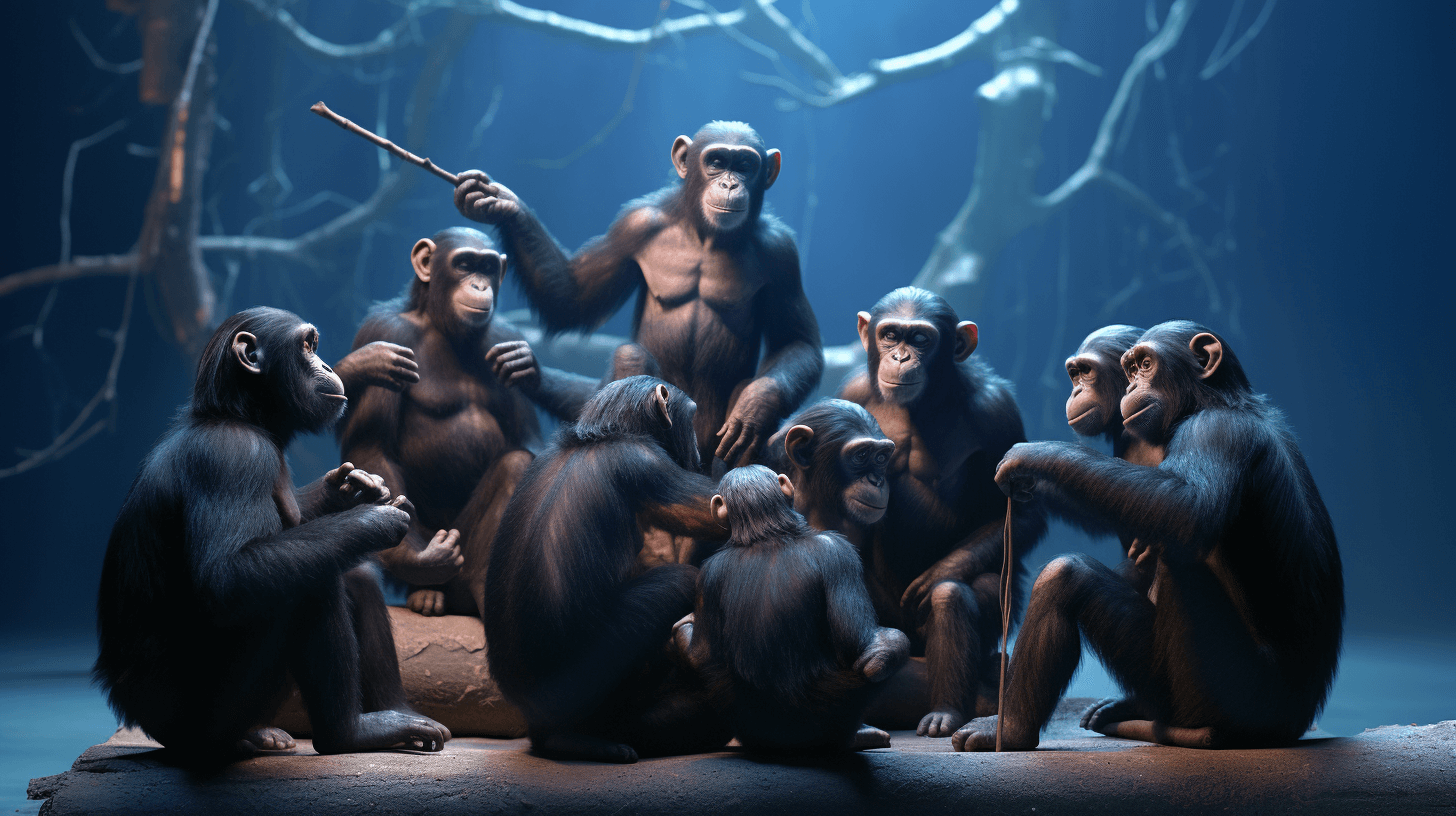

Da new kine genetic holoʻokoʻa of 290 peeps 🧑🤝🧑 wen suggest dat us humans wen pop up here and there, diffrent times 🕰️ and places 🌍, all ova Africa 🌍. Da scientists 👩🔬👨🔬 dem wen make da big reveal 🎉, get plenny complex da kine origins of us species 👥, no more just one argument dat modern humans wen come up from just one place in Africa during one point in time ⏳.

By checking out da genomes 🧬 of 290 peeps still living 🧑🤝🧑, da researchers wen conclude dat modern humans wen come down from at least two groups dat wen live side by side in Africa for one million years 📅 before coming together in several independent happenings all ova da continent 🌍. Da discoveries wen get published 📖 on top Wednesday in Nature.

“No more one single birthplace 📍,” said Eleanor Scerri, one evolutionary archaeologist at da Max Planck Institute for Geoarchaeology in Jena, Germany, who neva wen take part in da new study 📚. “Fo’ realz, dis one drives da last nail 🔨 into da coffin ⚰️ of dat idea 💡.”

Paleoanthropologists 👩🏫 and geneticists 👨🔬 wen find proofs dat point to Africa as da origin of our species 👥. Da oldest fossils 💀 dat might belong to modern humans, dating back as far as 300,000 years 📅, been found dea. Da oldest stone tools 🔨 used by our ancestors too.

Human DNA 🧬 also points to Africa. Da Africans still living get choke amount of genetic diversity compared with other peeps. Dat’s cause humans wen live and change ova time in Africa for thousands of generations before small groups — with comparatively small gene pools — wen start spreading out to other continents 🌎.

Inside da vast expanse of Africa, researchers wen propose diffrent places as da birthplace of our species 👥. Early humanlike fossils in Ethiopia led some researchers 👩🔬👨🔬 to look to East Africa. But some living groups of peeps in South Africa seemed to be really far related to other Africans, suggesting dat humans might get one deep history dea instead.

Brenna Henn, one geneticist at da University of California, Davis, and her buddies wen develop software 💻 to run large-scale simulations of human history 📚. Da researchers wen create plenny scenarios of diffrent groups existing in Africa ova diffrent periods of time 🕰️, then observed which ones could produce da diversity of DNA found in peeps still living today.

“We could ask what types of models are really plausible for the African continent 🌍,” Dr. Henn said.

Da researchers wen analyze DNA 🧬 from a range of African groups, including the Mende, farmers who live in Sierra Leone in West Africa; the Gumuz, one group descended from hunter-gatherers in Ethiopia; the Amhara, one group of Ethiopian farmers; and the Nama, one group of hunter-gatherers in South Africa.

Da researchers wen compare these Africans’ DNA 🧬 with da genome of a person from Britain. They also looked at the genome of a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal found in Croatia. Previous research had found that modern humans and Neanderthals shared a common ancestor that lived 600,000 years ago. Neanderthals spread across Europe and Asia, interbred with modern humans coming out of Africa, and then became extinct about 40,000 years ago.

Da researchers wen conclude that as far back as a million years ago, da ancestors of our species existed in two distinct groups. Dr. Henn and her buddies call them Stem1 and Stem2.

About 600,000 years ago, a small group of humans budded off from Stem1 and went on to become the Neanderthals. But Stem1 lasted in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years after dat, as did Stem2.

If Stem1 and Stem2 had been completely separate from each other, they would have accumulated a large number of distinct mutations in their DNA 🧬. Instead, Dr. Henn and her buddies wen find that they had remained only moderately different — about as different as living Europeans and West Africans are today. The scientists 👩🔬👨🔬 concluded that peeps had moved between Stem1 and Stem2, hooking up to have keiki 👶 and mixing their DNA 🧬.

The model does not reveal where the Stem1 and Stem2 peeps lived in Africa 🌍. And it’s possible that bands of these two groups moved around a lot over the vast stretches of time during which they existed on the continent. About 120,000 years ago, the model indicates, African history changed big time.

In southern Africa, peeps from Stem1 and Stem2 merged, giving rise to a new lineage that would lead to the Nama and other living humans in that region. Elsewhere in Africa, a separate fusion of Stem1 and Stem2 groups took place. That merger produced a lineage that would give rise to living peeps in West Africa and East Africa, as well as the peeps who expanded out of Africa.

It’s possible that climate shake-ups forced Stem1 and Stem2 peeps into the same regions, leading them to merge into single groups. Some bands of hunter-gatherers may have had to pull back from the coast as sea levels rose 🌊, for example. Some regions of Africa became dry, potentially sending peeps in search of new homes 🏠.

Even after these mergers 120,000 years ago, peeps with only Stem1 or only Stem2 ancestry seem to have survived. The DNA 🧬 of the Mende peeps showed that their ancestors had interbred with Stem2 peeps just 25,000 years ago. “It does suggest to me that Stem2 was somewhere around West Africa,” Dr. Henn said.

She and her buddies are now adding more genomes from peeps in other parts of Africa to see if they affect the models.

It’s possible they will discover other groups that endured in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, ultimately helping produce our species as we know it today.

Dr. Scerri speculated that living in a network of mingling populations across Africa might have allowed modern humans to survive while Neanderthals became extinct. In that arrangement, our ancestors could hold onto more genetic diversity, which in turn might have helped them endure shifts in the climate, or even evolve new adaptations.

“This diversity at the root of our species may have been ultimately the key to our success,” Dr. Scerri said. 👍🔑🏆

NOW IN ENGLISH

🦴🌍 Plenty of New Information About How The First Humans Came to Be 🧬

The new genetic study of 290 people 🧑🤝🧑 suggests that humans have appeared at different times 🕰️ and places 🌍 throughout Africa 🌍. The scientists 👩🔬👨🔬 unveiled that the origins of our species 👥 are complex, and it’s not just a single theory that modern humans arose from one place in Africa at one point in time ⏳.

By examining the genomes 🧬 of 290 living people 🧑🤝🧑, the researchers concluded that modern humans descended from at least two groups that lived side by side in Africa for one million years 📅 before coming together in several independent events across the continent 🌍. The discoveries were published 📖 on Wednesday in Nature.

“There is not just one single place of origin 📍,” said Eleanor Scerri, an evolutionary archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Geoarchaeology in Jena, Germany, who did not participate in the new study 📚. “This really drives the final nail 🔨 into the coffin ⚰️ of that idea 💡.”

Paleoanthropologists 👩🏫 and geneticists 👨🔬 have found evidence that points to Africa as the origin of our species 👥. The oldest fossils 💀 that might belong to modern humans, dating back as far as 300,000 years 📅, have been found there. The oldest stone tools 🔨 used by our ancestors were also found there.

Human DNA 🧬 also points to Africa. Living Africans have a significant amount of genetic diversity compared to other people. This is because humans lived and evolved in Africa for thousands of generations before smaller groups — with comparatively small gene pools — started spreading out to other continents 🌎.

Within the vast expanse of Africa, researchers proposed different places as the birthplace of our species 👥. Early human-like fossils in Ethiopia led some researchers 👩🔬👨🔬 to look to East Africa. However, some living groups of people in South Africa seemed to be distantly related to other Africans, suggesting that humans might have a deep history there instead.

Brenna Henn, a geneticist at the University of California, Davis, and her colleagues developed software 💻 to run large-scale simulations of human history 📚. The researchers created many scenarios of different groups existing in Africa over different periods of time 🕰️, then observed which ones could produce the diversity of DNA found in people living today.

“We could ask what types of models are really plausible for the African continent 🌍,” Dr. Henn said.

The researchers analyzed DNA 🧬 from a range of African groups, including the Mende, farmers who live in Sierra Leone in West Africa; the Gumuz, a group descended from hunter-gatherers in Ethiopia; the Amhara, a group of Ethiopian farmers; and the Nama, a group of hunter-gatherers in South Africa.

The researchers compared this African DNA 🧬 with the genome of a person from Britain. They also looked at the genome of a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal found in Croatia. Previous research had found that modern humans and Neanderthals shared a common ancestor that lived 600,000 years ago. Neanderthals spread across Europe and Asia, interbred with modern humans coming out of Africa, and then became extinct about 40,000 years ago.

The researchers concluded that as far back as a million years ago, the ancestors of our species existed in two distinct groups. Dr. Henn and her colleagues call them Stem1 and Stem2.

About 600,000 years ago, a small group of humans split off from Stem1 and went on to become the Neanderthals. But Stem1 lasted in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years after that, as did Stem2.

If Stem1 and Stem2 had been completely separate from each other, they would have accumulated a large number of distinct mutations in their DNA 🧬. Instead, Dr. Henn and her colleagues found that they had remained only moderately different — about as different as living Europeans and West Africans are today. The scientists 👩🔬👨🔬 concluded that people had moved between Stem1 and Stem2, reproducing 👶 and mixing their DNA 🧬.

The model does not reveal where the Stem1 and Stem2 people lived in Africa 🌍. It’s possible that bands of these two groups moved around a lot over the vast stretches of time during which they existed on the continent. About 120,000 years ago, the model indicates, African history changed significantly.

In southern Africa, people from Stem1 and Stem2 merged, giving rise to a new lineage that would lead to the Nama and other living humans in that region. Elsewhere in Africa, a separate fusion of Stem1 and Stem2 groups took place. That merger produced a lineage that would give rise to living people in West Africa and East Africa, as well as the people who expanded out of Africa.

It’s possible that climate changes forced Stem1 and Stem2 people into the same regions, leading them to merge into single groups. Some bands of hunter-gatherers may have had to pull back from the coast as sea levels rose 🌊, for example. Some regions of Africa became dry, potentially sending people in search of new homes 🏠.

Even after these mergers 120,000 years ago, people with only Stem1 or only Stem2 ancestry seem to have survived. The DNA 🧬 of the Mende people showed that their ancestors had interbred with Stem2 people just 25,000 years ago. “It does suggest to me that Stem2 was somewhere around West Africa,” Dr. Henn said.

She and her colleagues are now adding more genomes from people in other parts of Africa to see if they affect the models.

It’s possible they will discover other groups that endured in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, ultimately helping produce our species as we know it today.

Dr. Scerri speculated that living in a network of mingling populations across Africa might have allowed modern humans to survive while Neanderthals became extinct. In that arrangement, our ancestors could hold onto more genetic diversity, which in turn might have helped them endure shifts in the climate, or even evolve new adaptations.

“This diversity at the root of our species may have been ultimately the key to our success,” Dr. Scerri said. 👍🔑🏆