🖥️💔 Edward Fredkin, 88, Who Saw da Universe as One Big Computah, Dies

⬇️ Pidgin | ⬇️ ⬇️ English

An influential M.I.T. professor an’ an outside-da-box scientific theorist, he gained fame wit’ unorthodox views as one pioneer in digital physics. Edward Fredkin, who nevah gradumat’ from college but still became one influential professor of computer science at da Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wen pass away on June 13 in Brookline, Mass. He was 88. 😔🎓

His death, in one hospital, wen get confirmed by his son Richard. 💔🏥

Fueled by one limitless scientific imagination an’ one blithe indifference to conventional thinking, Professor Fredkin wen blaze through one ever-changin’ career dat could seem as mind-warping as da iconoclastic theories dat made him one force in both computer science an’ physics.

“Ed Fredkin wen get mo’ ideas per day dan most people get in one month,” Gerald Sussman, one professor of electronic engineering an’ longtime colleague at M.I.T., wen say in one phone interview. “Plenny of ’em wen be bad, an’ he woulda agreed wit’ me on dat. But outta all dose ideas, he wen have good ones too. So he wen have mo’ good ideas in one lifetime dan most people evah get.” 🤯💡📚

Aftah servin’ as one fighter pilot in da Air Force in da early 1950s, Professor Fredkin wen become one renowned, if unconventional, scientific thinker. He wen be one close friend an’ intellectual sparrin’ partnah of da celebrated physicist Richard Feynman an’ da computah scientist Marvin Minsky, one trailblazah in artificial intelligence. Even though he nevah gradumat’ from college, he still wen become one full professor of computer science at M.I.T. at da age of 34. Aftahward, he wen teach at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh an’ at Boston University. 🎓✈️🧠

But he nevah stay satisfied just stayin’ in da ivory tower. In 1962, Professor Fredkin wen found one company dat wen build programmable film readers, allowin’ computahs fo’ analyze data captured by cameras, like da Air Force radar information.

Dat company, Information International Incorporated, went public in 1968, bringin’ him great wealth. Wit’ his newfound riches, he wen buy one Caribbean island in da British Virgin Islands, an’ he wen fly dere in his Cessna 206 seaplane. But da island had no drinkable watah, so Professor Fredkin wen develop one reverse-osmosis technology fo’ turn saltwatah into fresh watah, which den became anothah one of his business ventures. 💰🌴✈️🌊💡

Latah on, he wen sell da property, Mosquito Island, to da British billionaire Richard Branson fo’ $25 million. 💸🏝️

Professor Fredkin’s life stay filled wit’ paradoxes, so it only right dat he wen have his own paradox credited to him. Fredkin’s paradox, as it known, posits dat wen you tryna choose between two options, da mo’ similar dey are, da mo’ time you go spend agonizin’ ovah da decision, even if da difference between da choices may be insignificant. On da oddah hand, when da difference is more substantial, you mo’ likely go spend less time decidin’. 🤔⌛️

As one early researcherin artificial intelligence half a century ago, Professor Fredkin foreshadowed da current debates ’bout hyper-intelligent machines.

“It goin’ take one combination of engineering an’ science, an’ we already get da engineering,” he Fredkin said in one 1977 interview wit’ Da New York Times. “Fo’ make one machine dat tink bettah den humans, we no need fo’ understand everythin’ ’bout humans. We still no understand feathers, but we can fly.” ✈️🧠🤖

As one startin’ point, he wen help pave da way fo’ machines fo’ beat Bobby Fischer an’ da oddah chess champs. As one developer of one early chess processin’ system, Professor Fredkin wen create da Fredkin Prize in 1980, offerin’ $100,000 to da first person who could develop one computah program dat can win da world chess championship.

In 1997, one team of IBM programmers wen accomplish dat feat, takin’ home da six-figure prize when deir computah, Deep Blue, wen beat Garry Kasparov, da world chess champion.

“Dere nevah was any doubt in my mind dat one computah go eventually beat da reigning world chess champion,” Professor Fredkin said at da time. “Da question always wen be when.” ♟️🖥️💰

Edward Fredkin wen born on Oct. 2, 1934, in Los Angeles, da youngest of four children of immigrants from Russia. His faddah, Manuel Fredkin, wen run one chain of radio stores dat wen fail during da Great Depression. His maddah, Rose (Spiegel) Fredkin, wen be one pianist.

As one cerebral an’ socially awkward kid, Edward nevah had interest in sports or school dances. He wen prefer fo’ lose himself in hobbies like buildin’ rockets, designin’ fireworks, an’ takin’ apart an’ puttin’ back togethah old alarm clocks. “I always wen get along well wit’ machines,” he wen tell Da Atlantic Monthly in 1988.

Aftah high school, he wen enroll in da California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, where he wen study undah da Nobel Prize-winnin’ chemist Linus Pauling. But his desire fo’ fly wen lead him away from college, an’ he wen leave durin’ his second year to join da Air Force.

Durin’ da Korean War, he wen train fo’ fly fightah jets. But his skills wit’ mathematics an’ technology wen land him work on military computah systems instead of combat. To furthah his education in computah science, da Air Force wen even send him to M.I.T. Lincoln Laboratory, one place where da military fund technological innovation.

An’ dat wen mark da start of his long tenure at M.I.T., where in da 1960s he wen help develop early versions of multiple access computahs as part of one Pentagon-funded program called Project MAC. Da program also wen explore machine-aided cognition, one early investigation into artificial intelligence.

“He wen be one of da world’s first computah programmers,” Professor Sussman wen say.

Professor Fredkin wen be chosen to direct da project in 1971 an’ wen become one full-time faculty membah shortly aftah.

As his career wen progress, he nevah stop challengin’ da mainstream scientific thinkin’. He wen make major advances in reversible computin’, one obscure field dat combine computah science an’ thermodynamics.

Wit’ two innovations — da billiard-ball computah model, which he wen develop wit’ Tommaso Toffoli, an’da Fredkin Gate — he wen show dat computation no need fo’ be irreversible. Dose advances suggest dat computation no need fo’ consume energy by ovahwritin’ da intermediate results of one computation, an’ it is theoretically possible fo’ build one computah dat no consume energy or produce heat. 💡⚖️🔥

But none of his insights wen spark mo’ debate den his famous theories on digital physics, one niche field where he wen become one leadin’ theorist.

His theory dat da universe can be seen as one giant computah, as described by da author an’ science writer Robert Wright in Da Atlantic Monthly in 1988, is based on da idea dat “information is more fundamental den matter an’ energy.” Professor Fredkin, as Mr. Wright wen say, believe dat “atoms, electrons, an’ quarks ultimately consist of bits — binary units of information, like da ones used in one personal computah or pocket calculator.”

As Professor Fredkin wen say in dat article, DNA, da fundamental buildin’ block of heredity, is “one good example of digitally encoded information.”

“Da information dat tell us what one creature or plant goin’ be is encoded,” he wen explain. “It get its representation in da DNA, yeah? Okay, now, dere one process dat take dat information an’ transform um into da creature.”

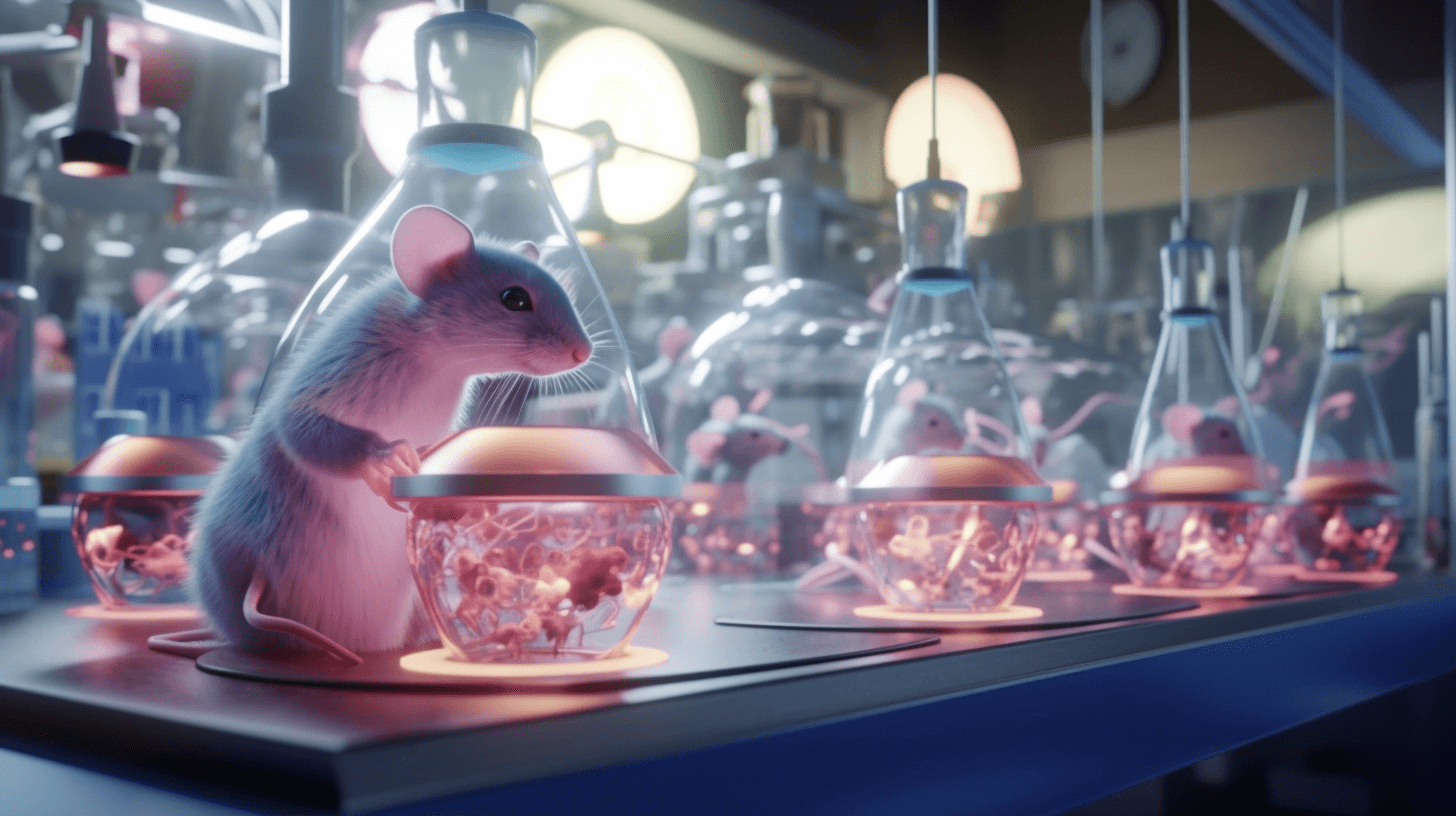

Even one creature as ordinary as one mouse, he conclude, “is one big, complicated informational process.”

Professor Fredkin wen divorce his first wife Dorothy in 1980. In addition to his son Richard, he stay survived by his wife Joycelin; one son, Michael; an’ two daughters, Sally an’ Susan, from his first marriage. He also get one brothah, Norman; one sistah, Joan Entz; six grandchildren; an’ one great-grandchild. 👪🌟💔

By da end of his life, Professor Fredkin’s theory of da universe still stay on da fringes, although it remain intriguin’. “Most of da physicists no tink it true,” Professor Sussman wen say. “I no even sure if Fredkin himself believed it was true. But no mattah wat, da way of tinkin’ still get plenny fo’ us to learn from.”

But his early views on artificial intelligence, on da oddah hand, seem mo’ prophetic wit’ each passin’ day.

“In da distant future, we no go know wat computahs stay doin’, or why,” he wen tell Da Times in 1977. “If two of ’em start talkin’, dey go exchange mo’ words in one second den all da words evah spoken by all da people dat evah live on dis planet.”

But even wit’ dat in mind, unlike many who warn of doomsday, he nevah feel one sense of existential dread. “Once get intelligent machines, dey no go care ’bout stealin’ our toys or dominatin’ us, jus’ like how dey no go care ’bout dominatin’ chimpanzees or takin’ nuts away from squirrels.”

In da end, Edward Fredkin’s legacy go continue to inspire an’ challenge scientists, engineers, an’ thinkers in da field of computah science, artificial intelligence, an’ beyond. His unorthodox ideas, his boundless curiosity, an’ his willingness fo’ go against da grain wen leave one lastin’ mark on da scientific community an’ da quest fo’ understandin’ da mysteries of da universe. 🌌🖥️🌟

NOW IN ENGLISH

🖥️💔 Edward Fredkin, 88, Who Saw da Universe as One Big Computah, Dies

An influential M.I.T. professor an’ an outside-da-box scientific theorist, he gained fame wit’ unorthodox views as a pioneer in digital physics. Edward Fredkin, who nevah graduated from college but still became an influential professor of computer science at da Massachusetts Institute of Technology, died on June 13 in Brookline, Mass. He was 88. 😔🎓

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his son Richard. 💔🏥

Fueled by a seemingly limitless scientific imagination an’ a blithe indifference to conventional thinking, Professor Fredkin charged through an endlessly mutating career that could appear as mind-warping as the iconoclastic theories that made him a force in both computer science and physics.

“Ed Fredkin had more ideas per day than most people have in a month,” Gerald Sussman, a professor of electronic engineering and a longtime colleague at M.I.T., said in a phone interview. “Most of them were bad, and he would have agreed with me on that. But out of those, there were good ideas, too. So he had more good ideas in a lifetime than most people ever have.” 🤯💡📚

After serving as a fighter pilot in the Air Force in the early 1950s, Professor Fredkin became a renowned, if unconventional, scientific thinker. He was a close friend and intellectual sparring partner of the celebrated physicist Richard Feynman and the computer scientist Marvin Minsky, a trailblazer in artificial intelligence. Even though he never graduated from college, he still became a full professor of computer science at M.I.T. at the age of 34. Later on, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and at Boston University. 🎓✈️🧠

But he never stayed content with just staying in the ivory tower. In 1962, Professor Fredkin founded a company that built programmable film readers, allowing computers to analyze data captured by cameras, such as Air Force radar information.

That company, Information International Incorporated, went public in 1968, bringing him great wealth. With his newfound riches, he bought a Caribbean island in the British Virgin Islands, and he flew there in his Cessna 206 seaplane. But the island had no drinkable water, so Professor Fredkin developed a reverse-osmosis technology to turn saltwater into fresh water, which then became another one of his business ventures. 💰🌴✈️🌊💡

Later on, he sold the property, Mosquito Island, to the British billionaire Richard Branson for $25 million. 💸🏝️

Professor Fredkin’s life was filled with paradoxes, so it was only fitting that he was credited with his own paradox. Fredkin’s paradox, as it is known, posits that when you’re trying to choose between two options, the more similar they are, the more time you spend agonizing over the decision, even if the difference between the choices may be insignificant. On the other hand, when the difference is more substantial, you’re more likely to spend less time deciding. 🤔⌛️

As an early researcher in artificial intelligence half a century ago, Professor Fredkin foreshadowed the current debates about hyper-intelligent machines.

“It requires a combination of engineering and science, and we already have the engineering,” he Fredkin said in a 1977 interview with The New York Times. “In order to produce a machine that thinks better than man, we don’t have to understand everything about man. We still dondon’t understand feathers, but we can fly.” ✈️🧠🤖

As a starting point, he helped pave the way for machines to checkmate the Bobby Fischers of the world. A developer of an early processing system for chess, Professor Fredkin in 1980 created the Fredkin Prize, a $100,000 award that he offered to whoever could develop the first computer program to win the world chess championship.

In 1997, a team of IBM programmers did just that, taking home the six-figure bounty when their computer, Deep Blue, beat Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion.

“There has never been any doubt in my mind that a computer would ultimately beat a reigning world chess champion,” Professor Fredkin said at the time. “The question has always been when.”

Edward Fredkin was born on Oct. 2, 1934, in Los Angeles, the youngest of four children of immigrants from Russia. His father, Manuel Fredkin, ran a chain of radio stores that failed during the Great Depression. His mother, Rose (Spiegel) Fredkin, was a pianist.

Cerebral and socially awkward as a youth, Edward avoided sports and school dances, preferring to lose himself in hobbies like building rockets, designing fireworks, and dismantling and rebuilding old alarm clocks. “I always got along well with machines,” he told The Atlantic Monthly in 1988.

After high school, he enrolled in the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, where he studied with the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling. Lured by his desire to fly, however, he left school in his sophomore year to join the Air Force.

During the Korean War, he trained to fly fighter jets. But his prodigious skills with mathematics and technology landed him work on military computer systems instead of in combat. To further his education in computer science, the Air Force eventually sent him to M.I.T. Lincoln Laboratory, a wellspring of technological innovation funded by the Pentagon.

It was the start of a long tenure at M.I.T., where in the 1960s he helped develop early versions of multiple access computers as a part of a Pentagon-funded program called Project MAC. The program also explored machine-aided cognition, an early investigation into artificial intelligence.

“He was one of the world’s first computer programmers,” Professor Sussman said.

Professor Fredkin was chosen to direct the project in 1971 and became a full-time faculty member shortly thereafter.

As his career developed, he continued to challenge mainstream scientific thinking. He made major advances in reversible computing, an esoteric field combining computer science and thermodynamics.

With a pair of innovations — the billiard-ball computer model, which he developed with Tommaso Toffoli, and the Fredkin Gate — he demonstrated that computation is not inherently irreversible. Those advances suggest that computation need not consume energy by overwriting the intermediate results of a computation, and that it is theoretically possible to build a computer that does not consume energy or produce heat.

But none of his insights stoked more debate than his famous theories on digital physics, a niche field in which he became a leading theorist.

His universe-as-one-giant-computer theory, as described by the author and science writer Robert Wright in The Atlantic Monthly in 1988, is based on the idea that “information is more fundamental than matter and energy.” Professor Fredkin, Mr. Wright said, believed that “atoms, electrons, and quarks consist ultimately of bits — binary units of information, like those that are the currency of computation in a personal computer or a pocket calculator.”

As Professor Fredkin was quoted as saying in that article, DNA, the fundamental building block of heredity, is “a good example of digitally encoded information.” 🧬💻🌌

“The information that implies what a creature or a plant is going to be is encoded,” he said. “It has its representation in the DNA, right? Okay, now, there is a process that takes that information and transforms it into the creature.”

Even a creature as ordinary as a mouse, he concluded, “is a big, complicated informational process.”

Professor Fredkin and his first wife, Dorothy Fredkin, divorced in 1980. In addition to his son Richard, he is survived by his wife, Joycelin; a son, Michael, and two daughters, Sally and Susan, from his first marriage; a brother, Norman; a sister, Joan Entz; six grandchildren; and one great-grandchild. 👪🌟💔

By the end of his life, Professor Fredkin’s theory of the universe remained fringe, if intriguing. “Most of the physicists don’t think it’s true,” Professor Sussman said. “I’m not sure if Fredkin believed it was true, either. But certainly there’s a lot to learn by thinking that way.”

His early views on artificial intelligence, by contrast, seem more prescient by the day.

“In the distant future we won’t know what computers are doing, or why,” he told The Times in 1977. “If two of them converse, they’ll say in a second more than all the words spoken during all the lives of all the people who ever lived on this planet.”

Even so, unlike many current doomsayers, he did not feel a sense of existential dread. “Once there are clearly intelligent machines,” he said, “they won’t be interested in stealing our toys or dominating us, any more than they would be interested in dominating chimpanzees or taking nuts away from squirrels.” 🤖💭🌍