🌫️🔍 Da Emergin Science of Tracin’ Smoke Back to Wildfires

⬇️ Pidgin | ⬇️ ⬇️ English

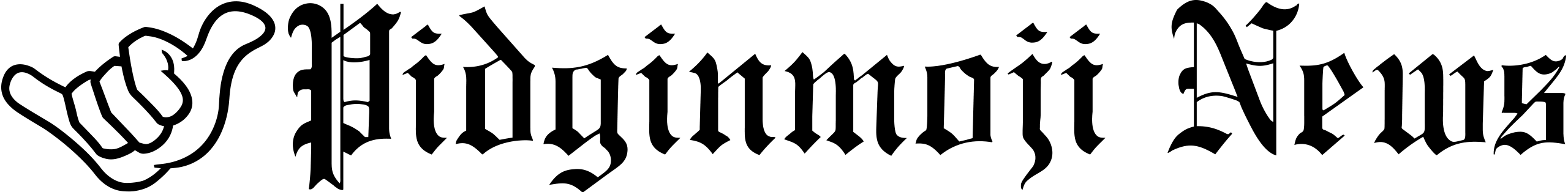

One upcomin’ study link smoke pollution acros’ da United States to individual wildfires an’ could help predict which fires goin’ be most harmful to public health. 👥🔥🌎 As smoke from wildfires crosses state an’ international borders more frequently, trackin’ an’ studyin’ it stayin’ increasingly important fo’ shapin’ air quality an’ health measures aroun’ da world. 🚧🌍🔬

One upcomin’ study from researchers at Stanford University offer one new way fo’ trace far-flung smoke an’ pollution back to individual wildfires of origin. 🔬🌫️🔍

What’s burnin’ in one wildfire determine what kind of pollution stay in da smoke. One forest fire burn differently from one fire in one swamp, o’ one fire that burn buildings. As smoke travel, its chemical composition may change with time an’ distance. 🌲🔥🌳 Da findings could help officials fo’ determine which wildfires goin’ be likely to have da biggest health consequences fo’ da greatest number of people, an’ fo’ allocate firefighting resources accordingly. 💼👩⚕️🚒 “We don’t find that fire suppression resources stay often spent on da fires that stay most damagin’ from one health perspective,” said Jeff Wen, one Ph.D. candidate in Earth system science at Stanford an’ da study’s lead author. 👨🔬💭📚 Othas have done similar research befo’, but at one much smaller scale. Da new study, not yet peer-reviewed, would be da first fo’ cover da whole contiguous United States, accordi’ to da authors. 👥🔬🌎

“Historically, we haven’t really been able to study those types of questions at one broad spatial, temporal scale,” Mr. Wen said. 📜🌍📊

It’s clear that wildfires stay become more frequent an’ intense in recent years, fueled in part by climate change’s role in dryin’ out many landscapes. Less clear to scientists stay been how smoke from these fires stay change ova time. Da new study show that as fires stay worsened, so stay their smoke: From 2016 to 2020, da U.S. population experienced double da smoke pollution that it did 10 years earlier, from 2006 to 2010. While da study focused on historical data, some of its methods can also be used fo’ predict where smoke from one new fire goin’ travel. 🔥📈🌬️ Da researchers focused on one pollutant called particulate matter, made of very small solid particles floatin’ in da air, which can enter people’s lungs an’ blood an’ lead to problems such as difficulty breathin’, inflammation, an’ damaged immune cells. 💨🫁⚠️

Usin’ their new method, Mr. Wen an’ his team rank all of da wildfires observed in da United States from April 2006 to December 2020 by da resultin’ smoke exposure. They find that da worst fire by smoke exposure durin’ dis period stay da 2007 Bugaboo Fire, which burn more than 130,000 acres in an’ aroun’ da Okefenokee Swamp, straddlin’ Georgia an’ Florida. 🔥🌊🔍 Dis initially surprise da researchers, since Western states tend to have more large fires. But da Eastern Seaboard stay more densely populated, so smoke from da Bugaboo Fire neva have to go far to affect many millions of people. Peatlands like da Okefenokee Swamp also tend to burn slowly, Mr. Wen said, releasin’ more particulate matter into da air. 🏞️🌫️🔥

Da worst fires in their rankin’ neva match up very well with da worst fires in traditional rankin’, such as acres burned o’ buildings an’ infrastructure lost. More firefightin’ resources neva necessarily deployed to da smokiest fires, eida. 🚒📊🔥 “We often suppress fires mainly because of structures

NOW IN ENGLISH

🌫️🔍 The Emerging Science of Tracing Smoke Back to Wildfires

An upcoming study links smoke pollution across the United States to individual wildfires and could help predict which fires will be most harmful to public health. 👥🔥🌎

As smoke from wildfires crosses state and international borders more frequently, tracking and studying it is increasingly important for shaping air quality and health measures around the world. 🚧🌍🔬

An upcoming study from researchers at Stanford University offers a new way to trace far-flung smoke and pollution back to individual wildfires of origin. 🔬🌫️🔍

What’s burning in a wildfire determines what kind of pollution is in the smoke. A forest fire burns differently from a fire in a swamp, or a fire that burns buildings. As smoke travels, its chemical composition may change with time and distance. 🌲🔥🌳

The findings could help officials determine which wildfires are likely to have the biggest health consequences for the greatest number of people and to allocate firefighting resources accordingly. 💼👩⚕️🚒

“We don’t find that fire suppression resources are often spent on the fires that are most damaging from a health perspective,” said Jeff Wen, a Ph.D. candidate in Earth system science at Stanford and the study’s lead author. 👨🔬💭📚

Others have done similar research before, but at a much smaller scale. The new study, not yet peer-reviewed, would be the first to cover the whole contiguous United States, according to the authors. 👥🔬🌎

“Historically, we haven’t really been able to study those types of questions at a broad spatial, temporal scale,” Mr. Wen said. 📜🌍📊

It’s clear that wildfires have become more frequent and intense in recent years, fueled in part by climate change’s role in drying out many landscapes. Less clear to scientists has been how smoke from these fires has changed over time. The new study shows that as fires have worsened, so has their smoke: From 2016 to 2020, the U.S. population experienced double the smoke pollution that it did 10 years earlier, from 2006 to 2010. While the study focused on historical data, some of its methods can also be used to predict where smoke from a new fire will travel. 🔥📈🌬️

The researchers focused on a pollutant called particulate matter, made of very small solid particles floating in the air, which can enter people’s lungs and blood and lead to problems such as difficulty breathing, inflammation, and damaged immune cells. 💨🫁⚠️

Using their new method, Mr. Wen and his team ranked all of the wildfires observed in the United States from April 2006 to December 2020 by the resulting smoke exposure. They found that the worst fire by smoke exposure during this period was the 2007 Bugaboo Fire, which burned more than 130,000 acres in and around the Okefenokee Swamp, straddling Georgia and Florida. 🔥🌊🔍

This initially surprised the researchers since Western states tend to have more large fires. But the Eastern Seaboard is more densely populated, so smoke from the Bugaboo Fire didn’t have to go far to affect many millions of people. Peatlands like the Okefenokee Swamp also tend to burn slowly, Mr. Wen said, releasing more particulate matter into the air. 🏞️🌫️🔥

The worst fires in their ranking did not match up very well with the worst fires in traditional rankings, such as acres burned or buildings and infrastructure lost. More firefighting resources were not necessarily deployed to the smokiest fires, either. 🚒📊🔥

“We often suppress fires mainly because of structures and immediate threat to life,” said Bonne Ford, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University who was not involved in this study. While it’s important to save lives and help rural communities in immediate harm’s way, it’s “short-term thinking” to focus only on those immediately dangerous fires and ignore others that may harm many people farther away through smoke exposure. 🏘️🔥👩🔬

Dr. Ford and others have studied wildfire smoke patterns, as well as the resulting exposure to particulate matter pollution. But the Stanford researchers have pulled off something new by putting the two together, she said, especially over so many years and so much land area. 👩🔬🌲🔍

One aspect of the study Dr. Ford took issue with was treating all human exposure to particulate matter in smoke the same, no matter where it happened. Some people are more vulnerable to air pollution, she said, depending on their age, pre-existing health conditions, other environmental factors, and whether they can take precautions such as wearing face masks outside and using air filters inside. Future research could combine Mr. Wen’s methods with existing vulnerability indexes, Dr. Ford said. 👩⚕️🔬📊

There are also more precise ways to track and predict where smoke travels, according to John Lin, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Utah who was not involved in the study. Aside from that, Dr. Lin thought the Stanford study would be very useful in figuring out the real human toll of wildfire smoke. 👨🔬🧪🔭

Smoke traveling long distances is “the new normal,” he said. This reality challenges the ways governments have historically dealt with air quality, through regulations like the Clean Air Act. Now that pollution is increasingly crossing borders, Dr. Lin said, the way that people manage air quality should evolve accordingly. 🌫️🛣️🌍